In this newsletter:

Deportation news

- Jackie Nanyonjo dies in Uganda as result of injuries inflicted during forced removal from UK

- New network monitors deportee abuses

- Ministers admit trying to forcibly remove tens of thousands of people

- Anti-deportation campaigns: ‘What kind of country do you want this to be?’

Protests for Migrant Justice (Europe)

- Afghan refugees hold protest placards outside a Bonn court

- “This is our battleground”: How a new refugee movement is challenging Germany’s racist asylum laws

- Refugee Protesters Tour Through Germany

- Bologna: “Siamo tutti clandestini”. Migrants demonstrate against racism and exploitation

Legal news

- UKBA to be scrapped

- EU (Afghanistan): the retreat from KA

- What will happen to human rights after the next election?

Events

- SOAS Detainee Support conference: A future without immigration detention? 26-27 April, London

- Young People Seeking Safety week including tour of Mazloom play: 24 June

Deportation News

Jackie Nanyonjo dies in Uganda as result of injuries inflicted during forced removal

From Movement for Justice (12 March):

Jackie Nanyonjo died in Uganda last Friday as a result of the injuries inflicted by the Home Office’s licenced thugs who deported her from Britain on 10th January. Jackie was a fighter for herself and for others: a lesbian who escaped from anti-gay persecution and a brutal forced marriage, and a member of the Movement for Justice.

In Britain she had been able for the first time to live and love openly as a lesbian; she was much-loved by a wide circle of friends who kept in touch with her after she was deported and who miss her deeply. All of us who knew her, or who didn’t know her personally but are determined to end the regime of racism and anti-immigrant bigotry that is responsible for her death, will fight to win justice for Jackie.

Jackie had been through the mental torture of the immigration and asylum system, with its arbitrary, subjective decisions and impossible demands to ‘prove that you are a lesbian’.

With all the limited avenues of Britain’s racist immigration laws closed to her and facing deportation to a country where it is a crime to be gay and where the political and religious leaders have whipped up a murderous anti-gay witch-hunt, Jackie’s only option was physical resistance. On 10th January, on Qatar Airways Flight QR76, Jackie fought bravely for her freedom with all the strength she could gather against four Reliance guards. She continued fighting when the guards drew curtains round their end of the plane to hide their crimes. She struggled for as long as she could until, beaten up, half strangled and bent double, she was overcome by the pain in her chest and neck and was unable to breathe.

When Jackie arrived at Entebbe Airport the ‘escort’ party handed her over to the Ugandan authorities, who held her for many more hours without any medical attention. When family members finally met her, long after the flight had landed, Jackie was in terrible pain and vomiting blood; they rushed her to a clinic, but in a country with widespread poverty and limited medical facilities they were unable to get the medical attention Jackie needed. Since Jackie was in hiding as a known lesbian, protected by relatives, every trip to a doctor or hospital involved a risk to her life and to the safety of her family. They were condemned to watch the agonising decline of Jackie’s health and strength over the next two months.

There have been protests outside the Home Office and UKBA in Croydon, calling for justice for Jackie and for the Home Secretary Theresa May to resign.

Read about the protests and see pictures here and here.

New network monitors deportee abuses

Kristy Siegfried, IRIN News

13 March 2013

The principle of non-refoulement, which prohibits the return of asylum seekers and refugees to a country where their lives or freedom would be threatened, is often referred to as the cornerstone of the 1951 Refugee Convention.

In reality, however, states that are party to these conventions frequently return unsuccessful asylum seekers to countries where they are likely to experience detention, persecution and even torture at the hands of authoritarian regimes.

Governments have shown little interest in what happens to rejected asylum seekers after they have been returned, often insisting that individuals are never deported to countries where they would be at risk. The UK Border Agency (UKBA) for example, has said that the UK’s asylum system delivers fair and high-quality decisions and that individuals determined to not need protection are returned to “a home country that has been found safe for them to live in”.

But limited research by civil society organizations has found not only that individuals in need of protection often are deported, but that some of the countries they are returned to are far from safe.

Post-deportation monitoring

Friederike Vetter of the Fahamu Refugee Programme and her colleague, Leana Podeszfa, who are managing the network, disagree with the UKBA’s contention that all asylum decisions made in the UK are just and correct. They argue that cuts in government funding to the legal aid system, starting in 2011, have put many legal aid providers out of business, significantly reducing the legal advice available to asylum seekers. A 2012 survey by Refugee Action, a nonprofit that provides legal aid to refugees, found that asylum seekers who received no legal advice ahead of their interview with the UKBA were 30 percent more likely to be refused asylum.

“There’s this cyclical argument of the Home Office, that they don’t remove people in need of protection,” said Lisa Matthews of the UK-based National Coalition of Anti-Deportation Campaigns. “But in fact people needing protection are removed simply because they haven’t been recognized by a broken [asylum] system. The only way to prove that false logic is to follow what happens to people when they are removed.”

While the need for post-deportation monitoring has long been recognized, monitoring efforts have been constrained by a number of factors, including a lack of communication between organizations in host countries and those in countries of origin.

Using its wealth of contacts in the refugee sector, Fahamu is in the process of identifying and recruiting organizations in both deporting and receiving countries to form an online directory. This will serve as the foundation of the Post-Deportation Monitoring Network.

Read full story here.

Ministers admit trying to forcibly remove tens of thousands of people

Diane Taylor, The Guardian

22 March 2013

System ‘in chaos’ as nearly half of enforced removals are cancelled, many of them after successful legal challenges

The government has admitted that it has tried to forcibly remove tens of thousands of people from the UK unlawfully.

The figures were disclosed to the Guardian after a freedom of information request which showed that almost half of the enforced removals the government attempted were cancelled.

Critics say the high number of cancellations and attempted unlawful removals are signs of a system in chaos.

In 2012, 14,435 enforced removals took place but between January and November 11,085 were cancelled. The figure for the full year is likely to be about 12,000 cancelled removals, almost half of the total.

Of those cancelled, 4,569 were halted because the courts said they were unlawful. In the past five years, 48,858 removals have been cancelled, 22,079 of them owing to successful legal challenges.

Emma Mlotshwa, of the charity Medical Justice, which provides support to detainees, many of whom face enforced removal, said: “This is a system in chaos. We deal with countless cases of enforced removals which are cancelled. The whole thing causes needless trauma to detainees. Taking someone to the plane and then back to a detention centre, keeping them under imminent threat of deportation, is inhuman and treats detainees no better than cargo.”

Read full story here.

Anti-deportation campaigns: ‘What kind of country do you want this to be?’

Jennifer Allsopp, 50:50 (Open Democracy)

25 March 2013

A new musical, Glasgow Girls, showcases the power of anti-deportation campaigns as both an expression of human solidarity and an essential device for holding states to account. But their key role, is to build support for an asylum system that upholds the rights of all.

What Glasgow Girls shows us is the stake we all have in the policies that affect asylum seekers: as friends, partners, teachers, neighbours, peers, but also as fellow humans. It’s not just about putting yourself in someone else’s shoes, but recognising the relationships which bind us with others, and recognising that we can all take action in our own shoes to respond to injustice for the good of all.

In a political context saturated with stigma against asylum seekers, Glasgow Girls show us that there are common principles around which we can come together: fairness, justice, dignity. It also reminds us that policies which criminalise and stigmatise asylum seekers, like detention and dawn raids, shame us all. In the words of one song, ‘what kind of country do you want this to be?’

It is important to recognise that, in spite of its force, the ‘one of us’ message which dominates Glasgow Girls also carries a range of assumptions which are not entirely unproblematic. Like most asylum advocacy, the show reifies the idea of the ‘good migrant’ and also raises questions about what role local communities should have in regulating access into and out of the national community. Because not all refused asylum seekers who have been treated unfairly by the system can rely on friends and neighbours to help fight their cause; not all can sing and dance, or bake, and not all of those who have been detained or forced into destitution by government policies are known to their community. Put more starkly still, some may simply not be deemed worth campaigning for. As one activist recently told me, ‘the guy was at serious risk of being sent back to torture, but the campaign took ages to get off the ground because, well, people thought he was a bit of an ass’.

Anti-deportation campaigns are a crucial expression of human solidarity, and most importantly, an essential device for holding states to account. This is the key motive for the campaign against the deportation of Agi in Glasgow Girls: ‘she’s not safe’, one of the girls cries, ‘the government is wrong…we have to convince them!’ But of course the way in which anti-deportation campaigns hold states to account will always remain partial; in and of themselves, they cannot be a comprehensive framework for justice. Glasgow Girls is explicit in its recognition of this.

The girls transition from campaigning to ‘save our neighbours’ to seeking to reform the political system to safeguard the rights of all. This is a familiar narrative, and an experience widely echoed in other social movements, such as the DREAMERs movement in the US. For the DREAMERs, anti-deportation campaigns, and the solidaristic bonds they represent, have proved to be a core activity in the quest for comprehensive immigration reform; they run anti-deportation campaigns to directly challenge the state, but also as a crucial tool to build solidarity for the wider dream. Policies which seek to dehumanise asylum seekers and distance them from the goodwill of residents, such as detention and dispersal, can, in some respects, be seen as an attempt to block the radical power of these ties.

Through its dismantling of the ‘us’ and ‘them’ binaries which permeate the media portrayal of asylum seekers, Glasgow Girls is a cultural fight-back to populist television shows like UK Border Force, and in this respect it’s remarkable. But it also sits snugly in the popular bildungsroman genre; it’s ultimately a ‘coming of age’ story, a tale of political becoming. I think that this is why I was able to identify so strongly with the musical, and why it’s had such great reviews more broadly. Glasgow Girls helps us to imagine stepping into the shoes of others, challenges us to walk in our own and to take action in support of an asylum system that is fair, just, and worthy of us all. Now finished in London, I hope sincerely that the show gets a national tour.

Read the full article here.

Protests for Migrant Justice (Europe)

Afghan refugees hold protest placards outside a Bonn court

AlertNet, 20 March 2013

Afghan refugees hold placards reading “Why are you killing my sisters and brothers”, “Finish bombardments on Afghanistan” and “Why are you killing us?”, stand outside a court in Bonn March 20, 2013, before the start of a lawsuit by relatives of victims of a deadly NATO air strike in northern Afghanistan ordered by a German commander. NATO aircraft opened fire on hijacked fuel trucks on the outskirts of Kunduz, killing as many as 90 people in an incident on September 4, 2009.

Afghan refugees hold placards reading “Why are you killing my sisters and brothers”, “Finish bombardments on Afghanistan” and “Why are you killing us?”, stand outside a court in Bonn March 20, 2013, before the start of a lawsuit by relatives of victims of a deadly NATO air strike in northern Afghanistan ordered by a German commander. NATO aircraft opened fire on hijacked fuel trucks on the outskirts of Kunduz, killing as many as 90 people in an incident on September 4, 2009.

“This is our battleground”: How a new refugee movement is challenging Germany’s racist asylum laws

Leoni Linek, Ceasefire

20 March 2013

Beginning about a year ago, Germany’s new refugee protest movement has had myriad experiences with arbitrary arrests and police brutality. Yet the activists’ determination is unbroken. After a march across the country last autumn, hundreds have been occupying central squares in various German cities, rallying against the brutal treatment faced by refugees in Europe.

Beginning about a year ago, Germany’s new refugee protest movement has had myriad experiences with arbitrary arrests and police brutality. Yet the activists’ determination is unbroken. After a march across the country last autumn, hundreds have been occupying central squares in various German cities, rallying against the brutal treatment faced by refugees in Europe.

While the protesters’ demands reflect the long-standing aims of the wider refugee movement, they are pushing them with increasingly militant methods, including squatting and hunger strikes. In Würzburg, refugees even stitched up their lips, an action the city had attempted though ultimately failed to ban (an administrative court ruled in favour of the refugees). Their protest is just one instance in the context of a diverse national movement that can hardly be described in its entirety here. What unites this movement, however, is the relentless activism of its protesters and the fact that they do not ask for charity but, instead, demand – and if necessary take – their rights.

Ten days ago, for example, the police attacked activists of the Refugees’ Bus Tour in a detention centre in Cologne, where they were distributing flyers, and detained 19 of them. They were held in solitary cells without food or medical treatment – one of the protesters had been unconscious and was injured when arrested – for twelve hours. And this is just the latest incident in a long series of arrests and attacks.

Nevertheless, the movement continues to push for its demands: a halt to all deportations, the abolition of mandatory residence (‘Residenzpflicht’) and the closure of all detention centres, which the activists have been calling ‘Lager’ (camp), angering many politicians who believe the term is too closely associated with ‘Konzentrationslager’, the German word for concentration camp. “They urged us not to say ‘Lager’”, Napuli Langa reports after a visit to the German parliament, “it reminds them of their own history which they don’t want to repeat”.

The protesters also demand the recognition of all asylum seekers as political refugees, arguing that all reasons compelling someone to flee their country, including socio-economic ones, are ultimately political. Unlike many earlier refugee protests in Germany, the activists frame their demands in a postcolonial context: ‘Our countries’ poverty is due to your countries’ exploitation’, is a message often heard at the movement’s protests.

Read the full piece here.

Refugee protesters tour through Germany

Haberler, 11 March 2013

For months, refugees in Germany have been protesting for better living conditions. Now, some activists have begun a campaign to mobilize communities affected by refugee policies and are touring the country in a bus.

The protest tour - dubbed the “Refugees’ Revolution Bus Tour” by its organizers - is arriving at its 11th stop. The group, consisting of 15 refugees and a handful of activists, has been on the road since late February, and their aim is to reach 22 cities by the end of March. Along the way, they are protesting for better living conditions in refugee shelters as well as advertising for a rally to be held March 23 in Berlin. The group’s members organized themselves spontaneously without the backing of a larger organization.

The protest movement got its start nearly a year ago,following the suicide of an Iranian, Mohammad Rhasepar, who hung himself on January 29, 2012, in a state-run facility in Bavaria. Prior to his death, his application to move to Kiel in northern Germany to be with his sister had been denied. Rhasepar’s story led asylum-seekers from across Germany to join together and demand more rights.

Read full story here.

“Siamo tutti clandestini”: Migrants demonstrate against racism and exploitation

Libcom.org, 25 March 2013

Despite heavy rain, around 1000 people marched through the streets of Bologna on 23 March 2013, in a general demonstration against the Bossi-Fini law, a restrictive law on immigration from 2002.

* The demands were clear:

The guarantee of a residence permit for everyone, not related to a job or income

* The end of daily institutional racism

* The end of the fraudulent act of indemnity

* The end of the farce of humanitarian permits and the fictitious right of asylum

* The permanent closure of all Centres for identification and deportation (CIE).

The call to demonstrate came from Coordinamento Migranti Bologna who wanted to give a strong signal to the newly elected parliament, by asking for the repeal of the Bossi-Fini law. “We’ve become stronger inside and outside our workplaces, we left behind the fear and we took the floor together, women and men. Now it’s time to take to the streets!”, said the appeal.

The demonstration on 23 March could be the first step, followed by a general strike by migrants and a national demonstration.

Read full post here and see more photos of the protest here.

Legal news

The UK Border Agency: after four years, a car crash in slow motion finally comes to a stop

Alan White, New Statesman

27 March 2013

The agency that’s caused so much misery and cruelty is to be restructured, but without proper resources its successor won’t be able to avoid the same mistakes.

The UK Border Agency was, of course, a body born of chaos. The problem was that all this rejigging never solved the fundamental problems of creaking systems and an insurmountable backlog. The new body, now at arm’s length and less accountable to parliamentary scrutiny, was shambolic and, as Theresa May would this week conclude, “secretive and defensive”.

Nowhere was this clearer than in its use of outsourcing. In the great game of providing jobs for the boys, UKBA was in a league of its own. Like many government entities, it felt the safest option was to give contracts to giant corporations, regardless of expertise or know-how. So this month we learned that G4S, which has no previous experience of providing social housing, is struggling to provide housing for asylum seekers. One of the firm’s subcontractors has already resigned because it is not up to the task, while two others have “expressed concerns” about being able to provide the requisite services.

But incompetence is one thing - cruelty quite another. The fact the new body was kept at arm’s length lead Theresa May to conclude it had created a “closed, secretive and defensive” culture. Staff from sub-contractor Reliance were transporting Roseline Akhalu when she ended up pissing all over herself because she wasn’t allowed to use a toilet. Staff from Tascor - which superceded Reliance - allegedly beat Marius Betondi and broke his nose during a failed deportation attempt. That was one of thousands of distressing cases, the product of a system in chaos.

The failure to prosecute G4S staff over the death of Jimmy Mubenga has been described as “perverse” by the former Chief Inspector of Prisons. Just as it failed to protect victims of torture, so the system failed to protect victims of slavery. The right-wing Centre for Social Justice (CSJ) found a litany of flaws in UKBA’s procedures and concluded that “too often the CSJ has been told that UKBA involvement in the . . . process acts as a major barrier to victims [of slavery] to make a referral.”We have been told about the restructuring plans. But restructuring last time round only made the mess worse, because the root causes of the problem weren’t addressed.

Read the full article here.

EU (Afghanistan) - the retreat from KA

Free Movement blog, 26 March 2013

Like me, readers may have detected some uncertainty from the First-tier and Upper Tribunals about how best to determine claims of former UASCs from Afghanistan in light of EU and others (Afghanistan). In EU the Court of Appeal, Sir Stanley Burnton giving the only substantive judgement, determined the individual claimants’ appeals from KA (Afghanistan) and in doing so closed off avenues of redress which had briefly seemed possible following KA.EU, in its conclusions and indeed its tone, is a very negative judgement. However, having said that, I think that it may be relatively easy to persuade Tribunals that it is, in fact, very narrow in its scope.Read more at Free Movement.

What will happen to human rights after the next election?

Roger Smith on UK Human Rights Blog

20 March 2013The pace on human rights is being forced by Theresa May, seen by some as the Tory leader in waiting. She made it clear at the weekend that both the HRA and the European Convention which it introduces into domestic law are under fire.

“‘It’s my job to deport foreigners who commit serious crime – and I’ll fight any judge who stands in my way”.

Actually, the Home Secretary’s job can be put with somewhat more precision. It’s her role to follow UK law in relation to the deportation of foreigners. Her frustration comes from the fact that she amended the Immigration Rules to fit the result that she wanted but not the supporting legislation. Under the Human Rights Act, the judges are bound by the legislation but not the rules. The latter were passed after a debate by a vote in the House of Commons – not having gone through the full process of Parliamentary scrutiny with votes in both Houses of Parliament and detailed examination. If statute authorised deportation at the Home Secretary’s direction then every UK judge would allow it.

So, why did Mrs May not seek the powers that she coveted in legislation? Probably because she thought she might not get it through the House of Lords. As she will know perfectly well, the doctrine is Parliamentary Sovereignty, not ministerial or House of Commons supremacy. Ministers who want to make decisions of any kind simply have to get statutory approval and they are home free. Judges remain in their traditional role as lions under the throne. Their only enhanced powers in relation to human rights relates to a power to overrule secondary legislation and to declare that primary legislation is not, in their view, compatible with the European Convention.The Human Rights Act has played an enormous role in making our society more transparent and our institutions more accountable.

Read the full piece here.

Events

SOAS Detainee Support conference 2013:A Future Without Immigration Detention?

26 - 27 April 2013

SOAS University, LondonFull details here.

Young People Seeking Safety week

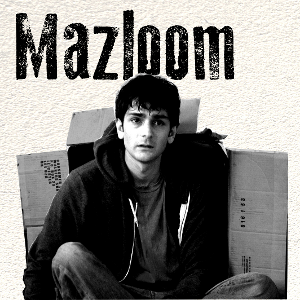

including tour of Mazloom play: 24 June

YPSS week is a week of action celebrated through local events across the UK. YPSS week 2013 will start on June 24.

YPSS week aims to bring positive local attention to the issues of young asylum seekers; encourage conversation and action across the nation, provide a platform for young people to share their experiences and express their concerns; and act as a showcase for the talents, creativity and diversity of young people seeking safety and those that support them.YPSS Week events are taking place all over the UK, and include art exhibitions, theatre performances, poetry, panel discussions and much more.

One of the major events of this year’s YPSS week will be a national tour of Mazloom, the drama performance exploring how it feels to be a young refugee facing deportation to Afghanistan.

Mazloom is a portrait of a young refugee, alone in London, whose life is being torn apart by the impending prospect of deportation to Afghanistan, where indiscriminate violence and Taliban intimidation await.This short, powerful theatre performance incorporates immersive film footage to recreate the long perilous journey to Europe and the agonising wait for the life-or-death decision on their asylum claim.

Mazloom is based on the experiences of young Afghans, who as children were forced by war to leave their family and home to seek safety in the UK.

“Mazloom is a tender and honest piece of the human story behind an issue that is so often reduced to statistics and political manifesto soundbites” Hamish Jenkinson, director of the Old Vic TunnelsFor more information, contact [email protected]